A Conversation

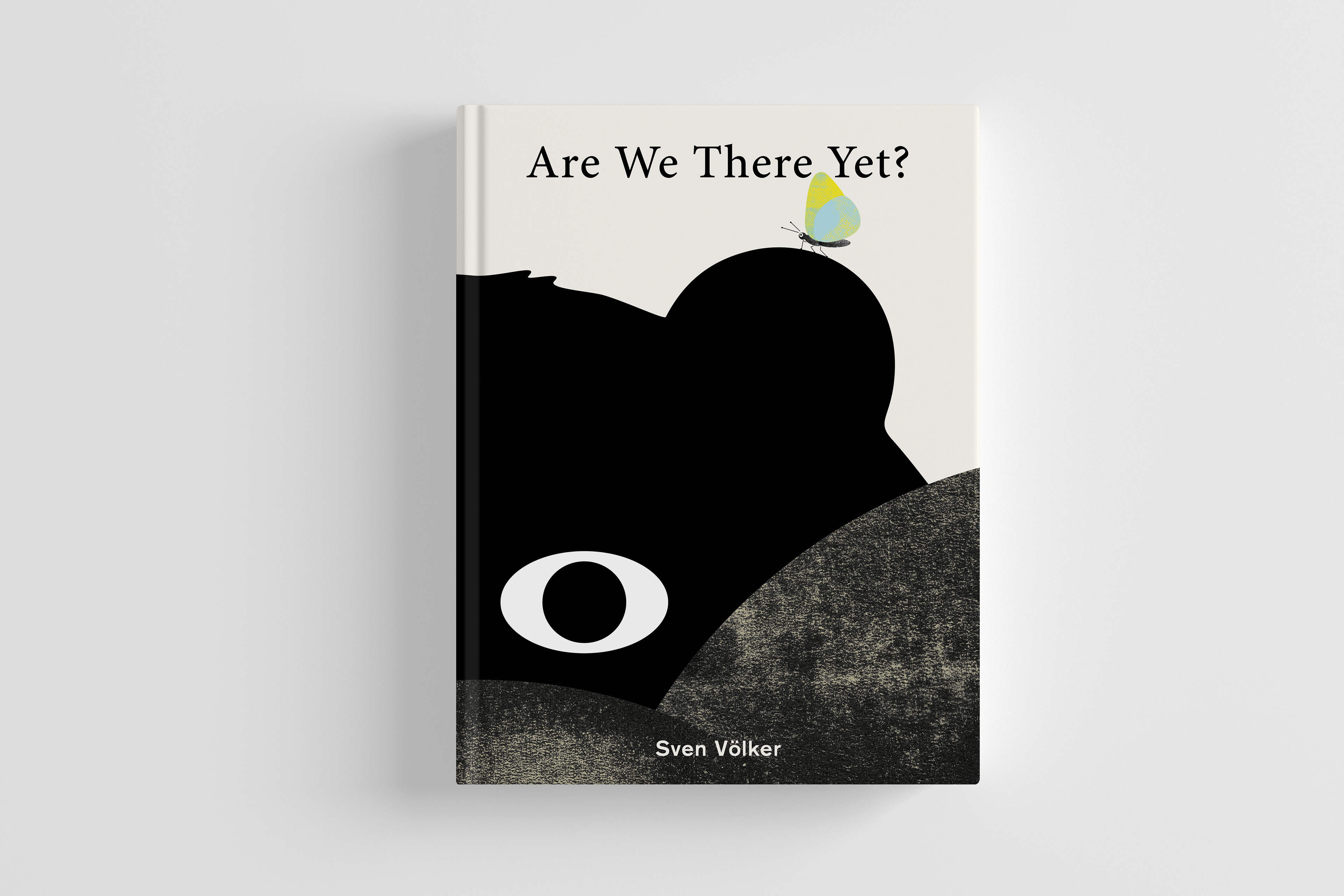

"A Million Dots" won the New York Times Best Illustrated Children's Book Award. In his new picture book "Are We There Yet?", Sven Völker sends a big bear and a small butterfly on a very long journey. A conversation about the new story, the magic of 'making' picture books and his own surprising detours in life.

"This book has become a thinking exercise about life."

"A sensitive script, touches of humor, and a captivating design combine for an excursion readers will want to repeat."

Kirkus Review

Your new picture book is a beautiful story titled "Are We There Yet?". What is it about?

It is the story of a butterfly that takes her friend, a bear on a great journey. It is a story about friendship and patience and about the cycle of life. The both of them are, of course, very different. The bear is big and heavy and the butterfly is very light and small. Both experience the same journey very differently and even though they are always traveling side by side, the challenges and difficulties are not the same for each of them. I found it exciting to write and illustrate a book that is only at first glance an adventure and in reality consists of many, very different facets. This book has become a thinking excercise about life. And like all great journeys, this is one big cycle, where you don't arrive at a final destination, but at a starting point for the next, great trip.

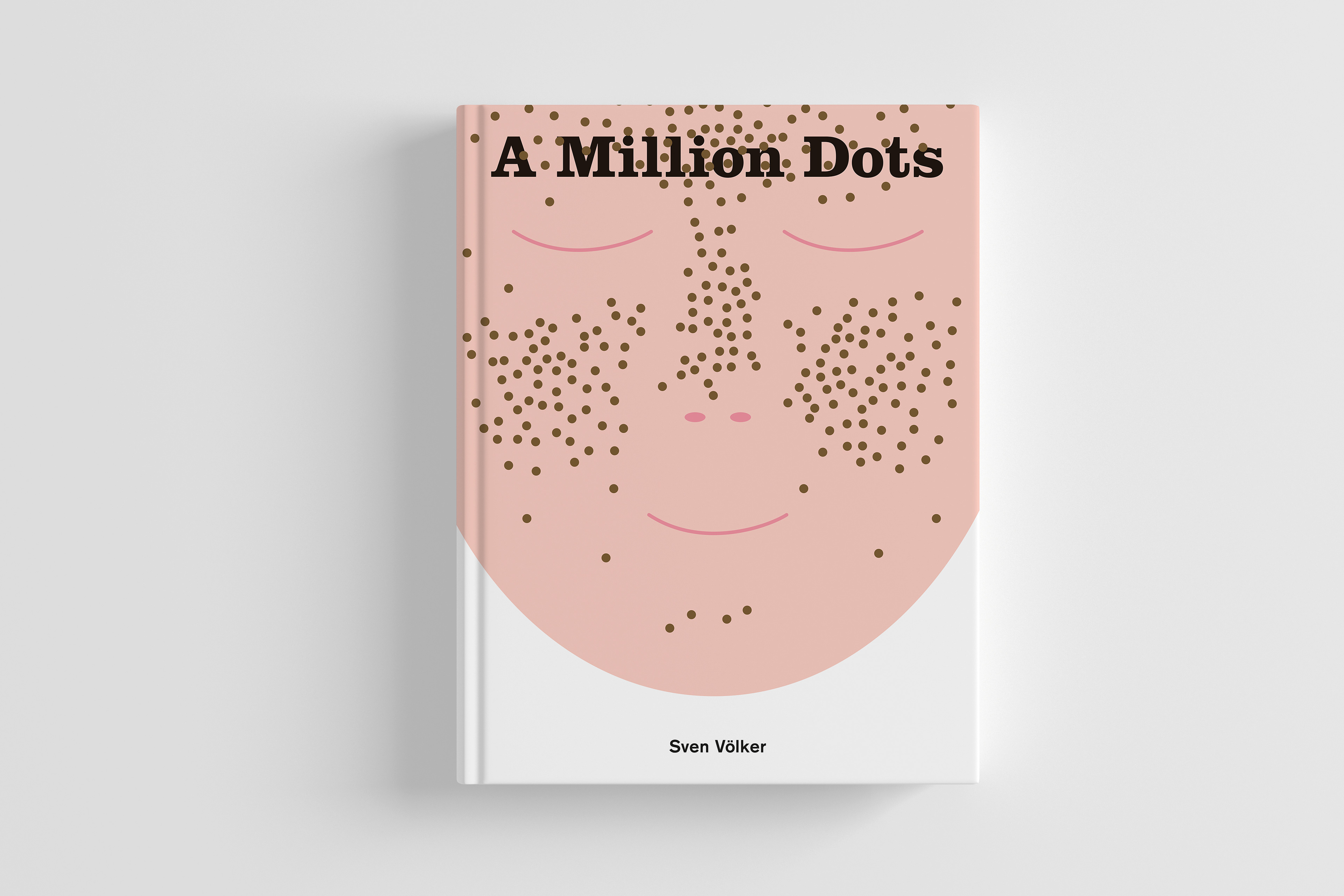

Your book "A Million Dots" won the prestigious New York Times award, was it a big surprise?

Yes definitely. I didn't expect it at all, it was only my second picture book and I just had arrived in the children's books universe. The "A Million Dots" is about numbers and mathematics, but actually it's also about understanding our world in its endlessness. On each page, the number doubles, and so you quickly get from one, two and four to the really big numbers within its 40 pages. Each number is not only written out, but also visualized by the exact number of dots in the illustrations. In the end, you hold more than a million little dots in your hands, which is fascinating. I love books that grow beyond themselves and end up being much more than just a story.

Exponential growth is not just a mathematical principle. It also describes the many crises of our times very clearly - from climate change to the Covid epidemic. By the way, I find the idea of exponential growth not only threatening but also very reassuring. There is always hope that our good ideas will multiply and have an impact just as fast as our bad actions have had. I firmly believe that we can take control of our destiny and that of our planet and change it for the better.

You have not always been a children's book author and illustrator?

No, I started out as a graphic designer, creating corporate identities for big companies and institutions. But I always worked on personal projects as artist and author but I kept most of it to myself. I kept asking myself where the connection lies between art and design - where both worlds can meet. I find the work and life of artists such as Corita Kent, Derek Jarman, Bruno Munari and Lawrence Weiner very fascinating. And funnily enough I originally wanted to become: a picture book illustrator in the first place. In my first week at art school I sat in the illustration class and watched the other students drawing with such talent, I was pretty intimidated. I wasn't at all as good as they all were and quickly I ended up in the typography class. I took a very long detour before I was able to publish my first picture book a few years ago.

Until ten years ago, I ran my own design company in Berlin Mitte where we worked for clients like the Japanese car manufacturer Suzuki. Those were pretty wild times. We were such a small office located in the basement of a furniture store and worked on huge projects for one of the really big global car companies. We did a lot of exciting design, we won many awards and also made good money. But in the long run, it didn't feel right to only work for commerce. Not to mention the automobile topic which fascinated me immensly at the beginning but over time has lost its fascination almost completely.

"I believe that there is no difference between art and design"

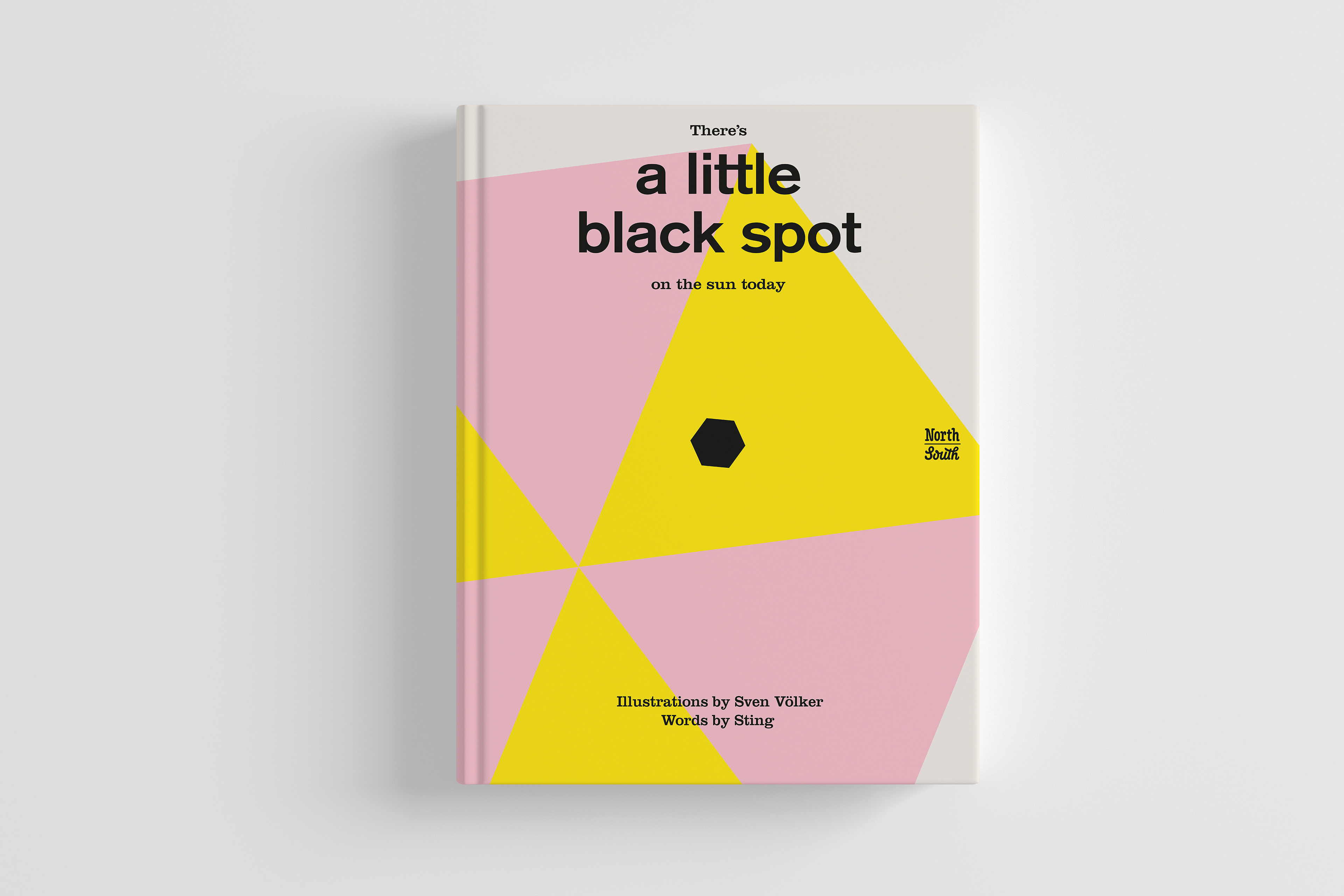

Then you created your first picture book. And you did this not just with any author, but with singer and The Police frontman Sting.

At the time, our oldest son was suffering from a chronic kidney disease and for many years we spent a lot of time in the hospital. I always picked him up at school at noon and then we went to the hospital together by car. We had a nice routine of turning up the car radio and singing along. At some point the song "King of Pain" by "The Police" was playing on the radio. They were the heroes of my youth and of course I sang along loudly. My son asked me a little irritated: "What is he singing?" and I translated the sentence into German: "King of Pain - König der Schmerzen". Whereupon he said without hesitation, "that's me - I'm the king of pain." This moved and touched me deeply and I started to illustrate Sting's lyrics on that very evening. I added my visual forms to his linguistic images about pain. He writes so beautiful sentences like "There's a dead salmon frozen in a waterfall". In our words and pictures we describe very different pains, but they offer the readers - both children and adults - a reason to talk about the difficult topic of pain. I gave the original illustrations to my son and hung them in his room. Later, I sent a second set of prints to Sting to New York. I thought to myself, "If you don't ask, you'll never know what the answer would have been." A few weeks later, an enthusiastic email arrived: Sting was all excited and really wanted to turn it into a picture book.

What fascinates you about making picture books?

I think, the concept of 'visual thinking' is what excites me the most about it. I think and work in words and in pictures at the same time. They play with each other and also they fight about what place each gets on the page. When words and images meet in a book it is like a chemical reaction. Sometimes something beautiful happens, sometimes something surprising, and sometimes it explodes. In graphic design, on posters for example, this is a classic technique. Ideally, the designer tricks the viewer's brain. It works like this: When we read a word, we search our memory for suitable images to go with it - we can't help it, and for each of us, for example, the sentence "I finally arrived at home" means something completely different and we associate it with different emotions and associations. But when we connect this sentence with the illustrator's visual idea of the 'home' he creates, a new variation of our memories is born. In the reader's imagination, words and images create a new, extended world. This is like magic. But there can also be conflicts, for example, if we read the word dog but next to it see the drawing of a cat, the both collide in our brain and we resolve this conflict by building our own little story around it. This is, how you could reduce the entire history of graphic design to this simple but ever-changing encounter of word plus image. With picture books, there's in addition the fact that most of the times just one of the readers can really read and the other can't yet. Then you talk with your kids about the story and think it through and extend it together.

You've been teaching graphic design at university for many years. How did it come about and what is particularly important to you in your teaching?

I was just 27 years old when I first stood as a professor in front of students, some of whom were older than me. This taught me very early on not to take myself too seriously and instead take them - my students - all the more so. For me, studying art and design is always a study at eye level between teacher and student. We ask each other questions and try to find more than one answer. Design and art are not disciplines in which prefabricated and tried-and-tested knowledge can help you much. Instead, it is always about finding a new way, a new idea and a new, previously unknown image for something. A pilot flies a plane according to proven standard procedures, and we expect exactly this. An artist though, who produces art according to a standard procedure will hardly ever create interesting work.

Together with my students I have been publishing "Some Magazine" for many years and we do this with quite some success. It is an independent magazine about the intersection between art and design and about inventing pictures. The students research and write all articles themselves, they also design and produce the magazine. And then finally two times every year, we celebrate when we see it sitting on the shelves at the MoMA bookshop in New York, at Palais de Tokyo in Paris or at Doyoureadme?! in Berlin.

New Book coming Spring 2023

Winner of New York TImes Best Illustrated Children's Books 2019

Based on a text written by Sting

"Little by little, I'm getting better at

enjoying uncertainty in my creative process."

You also make paintings and sculptures. How would you describe your process in art.

I think the process of inventing a visual world is very similar - whether you're designing a poster, making a picture book, or painting a canvas. When an idea of something arises in my head, it sometimes takes a while until I finds the right medium for it. I first try out my ideas on paper, completely analog, either with pen and words, or in quick drawings, for which I often use oil pastels and watercolors. Sometimes that's it and it stays as a sketch in my drawer. But sometimes an idea can go further. My picture books often very quickly make a step from the analog sketches to digital illustrations. In the end all of my picture book illustrations are created on a computer. Only some elements in "Are We There Yet?" were analog monotype prints I did on an old printing press.

My canvases and sculptures are a different thing. For my large-format paintings, for example, I use a special technique with silk tissue paper and acrylic paint. The colored paper makes the shapes on the canvas appear almost like printed. Only when you look at the picture from close up you can see how it is made. I am now working for some time on a series of small sculptures that resemble scaled models of billboards. In their small oak display cases, they seem somewhat fallen out of time. They look like models of life-size originals on some highway that don't exist or never have.

Sometimes I know exactly where I want to go with a piece of work, sometimes I just drift. Little by little, I'm getting better at enjoying uncertainty in my creative process. I also prefer not to make too many pieces and work too fast. I have learned that my best projects always had a long time to grow in my head.

What's next, what are you working on now and what are you interested in for the future?

I will stay in the field of picture book making and I will explore how I can develop the concept and form of these books further. Why should I ever stop making them as they are such a joy to produce? I don't know how many more books I will succeed in making, but if there are a few more good stories in this world, that's certainly not a bad thing.

I think that we - more than other generations before us - have a really tricky task to complete. As humans, we will have to find a new and less destructive role in our world. We are facing a future that will be governed by different ideals and mechanisms than the past has. Instead of growth, discovery and conquest, there will have to be other motivations for human curiosity. In my idea of a balanced and peaceful world, culture plays an essential role - I am deeply convinced of that. In my opinion, such a concept of culture is not one that is limited to museums, opera houses and bookshelves, but an idea that permeates and enriches all areas of our lives.

I believe that a vivid and multifaceted culture is able to bring communities together and heal conflicts, it can create a sense in life, it can give birth to dreams and it also helps us to achieve them. And if a picture book makes you as a child take a first tiny cultural step right at the beginning of your life - then ‘Picture Book Maker‘ seems a more than wonderful profession for me.

Haven't Seen Myself In Ages - Installation at Grand Palais Bern, Switzerland